Burned out and thirsting for a new adventure, Dr. Dilan Ellegala took a six-month sabbatical from his neurosurgery practice in 2006 to work in a missionary hospital deep in the Tanzanian bush.

But when he arrived, he was shocked to find that Tanzania had only three brain surgeons for its entire population of 45 million. Meantime, the missionary hospital where he planned to work lacked even the most basic surgical tools.

“People with head injuries and brain tumors healed on their own, or more often, died,” Ellegala said recently.

When confronted with a patient with a severe head injury, Ellegala refused to let the case go.

Child in Tanzania with head injury from hyena bite

Cover of Book.

He bought a tree saw from a farmer, sterilized it, and then used it to cut open the patient’s skull. He treated the wound and save the farmer’s life. In other cases, Ellegala used a camper’s headlamp as an operating light and metal rods from the ambulance garage to fuse spines.

“Yes, I saved a few lives, but I quickly realized that there were too many neurosurgery patients for one person to save,” he said. “I needed to teach someone what I knew.”

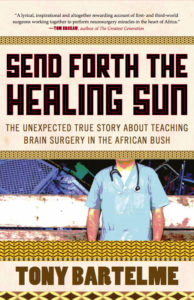

Ellegala’s quest to teach brain surgery in the African bush is the subject of Send Forth the Healing Sun: The Unexpected True Story About Teaching Brain Surgery in the African Bush, published recently by HarperCollins in Toronto.

Written by Tony Bartelme, a three-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, the book describes how Ellegala trained a clinician to do basic brain surgeries, and then how that clinician taught another local Tanzanian, who went on to teach a third.

“It’s a teach-a-man-to-fish story but with brain surgery,” Bartelme said.

Such success fueled Ellegala’s decision to create a nonprofit called Madaktari Africa. Through Madaktari (Swahili for doctors) Africa, more than 500 health care professionals have traveled to Tanzania to teach neurosurgery, heart surgery and other medical procedures.

Dilan in Dar es Salaam explaining his program

Author Tony Bartelme

“The old model of sending doctors on medical missions to treat people just doesn’t work,” Ellegala says. “You should always teach first.”

Ellegala’s pioneering spirit is rooted in his upbringing. When he was six, his parents, Somisara and Chitra Ellegala, moved from their home in Kandy to South Dakota, hoping to provide their three children with more educational opportunities. Somisara, who died last year, often spoke about how he arrived in the United States with just $20. They impressed upon their children the value of education and hard work.

Ellegala says he knew he wanted to be a doctor since he was four years old in part because of his uncle, a prominent doctor in Kandy. After graduating from the University of Washington’s medical school, Ellegala entered the University of Virginia’s neurosurgery residency program, one of the toughest in the country, and then capped his educational resume with a cerebrovascular neurosurgery fellowship at Harvard Medical School.

Dilan Ellegala and clinician he taught Emmanuel Mayegga

In addition to his global health work, Ellegala is at the forefront of efforts to use ultrasound technology to do minimally invasive spinal surgery. Current surgical techniques can still be brutal affairs, with surgeons using bone cutters to access the spinal canal and rods and plates to add stability in the bone’s absence. While effective, fusing the spine eliminates the spine’s natural capacity to bend and twist, putting pressure on other vertebrae.

Ellegala doing modern neurosurgery in US

Ellegala wasn’t satisfied with these techniques and began working with instruments that use ultrasonic energy to melt away bone. While sound waves can sculpt bones with extraordinary precision, sound waves bounce off nerves, leaving them unharmed. Patients are often able to leave the hospital within a day or two, instead of much lengthier stays.

“We’re calling this the ultrasonic revolution,” he says.

He recently founded a company in Lynchburg, Virginia, called SonoSpine to treat patients and share this technology with other surgeons. He lives there with his wife Carin, his three children and mother, Chitra, balancing family life with his interests in global health and new medical innovations.