Like Funny Boy, Hungry Ghost may be partly biographical. For instance, the way the newly-immigrated Shivan looks at Toronto, the city’s mad rush to cash in on the immigrant waves by offering shoddily-constructed houses, early Tamil immigrants exploiting their own kind to make a fast buck, overt racial bias, and the chaos in the emerging gay life in Toronto may have been drawn from his own diary. Shivan wins readers’ sympathy for his life’s inescapable ‘karmic’ effects (shades of Thomas Hardy) that shape his battles. He is a lone fighter not willing to give up and wins at a heavy emotional cost. At the end he goes to his ailing grand mother’s bedside to look after her, symbolically vacuum cleaning his life for a new beginning. Hungry Ghost is the best book so far by this young Sri Lankan-born writer who has shown maturity in his craft over the years and shows promise of a great future. At 48, night is still too young for him.

Sri Lankan-born Canadian author Shyam Selvadurai was named among five finalists by the City of Toronto and the Toronto Public Library for the 2014 Toronto Book Awards, which honour authors of books of literary or artistic merit that are evocative of Toronto. This year marks the 40th anniversary of the Toronto Book Awards.

Sri Lankan born Selvadurai is among five finalists for Toronto's top prize.

Sri Lankan-born Canadian author Shyam Selvadurai was named among five finalists by the City of Toronto and the Toronto Public Library for the 2014 Toronto Book Awards, which honour authors of books of literary or artistic merit that are evocative of Toronto. This year marks the 40th anniversary of the Toronto Book Awards.

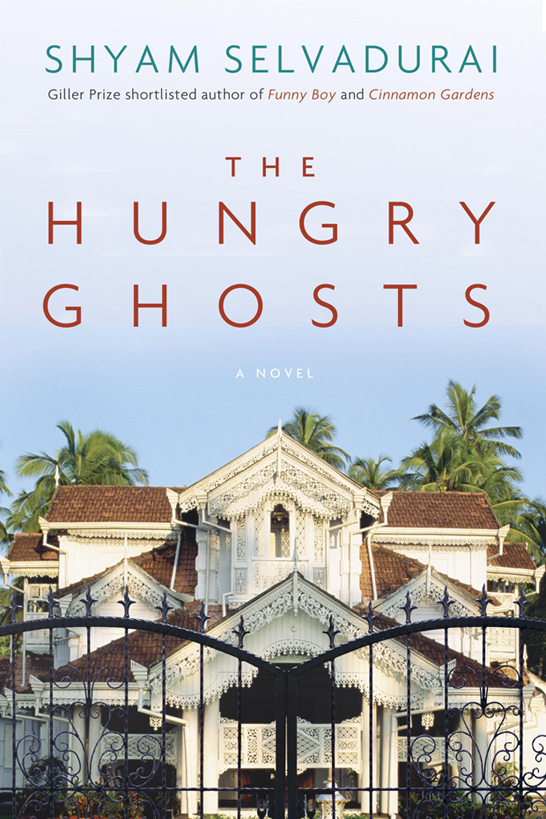

Selvadurai was named for his novel The Hungry Ghosts, published by Doubleday Canada.

Each finalist will receive $1,000 and the winning author receives $10,000. The winning author will named on October 16 at the Toronto Reference Library’s Bram & Bluma Appel Salon. The city invited members of the public to celebrate the evening awards celebration hosted by CBC Radio’s Gill Deacon.

Selvadurai will join his fellow his fellow finalists to read at The Word On The Street book and magazine fair. The event will take place on Sunday, September 21 at Queen’s Park North from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.

‘Hungry Ghosts’ Shyam’s best novel so far

The Hungry Ghosts, published by Doubleday Canada.

A boy is riding in his Sinhala grandmother’s car. His name is Shivan. How has this Sinhala boy acquired a Tamil name, we wonder! As the story unfolds we know that Shivan is a child of a Sinhala mother and a Tamil father. The troubles start there.

Sri Lanka is plagued by ethnic violence forcing minority Tamils to flee wherever they can find a safe haven. Even the Sinhala women married to Tamils and their offspring like Shivan and sister Renu were not spared in 1983 riots. Thanks to his grandmother Daya’s thugs Shivan’s family is protected during the unrest.

Sri Lankan-born Shyam Selvadurai’s fourth work of fiction is based on his troubled native land and his chaotic growing up in Canada. Michael Ondaatje’s Anil’s Ghost is based on the same violent period in Sri Lanka’s recent history. President R. Premadasa’s government was fighting two enemies. On one side the Liberation Tigers were trying to carve out a separate state in the north while in the south the JVP or the People’s Liberation Front unleashed their brutal campaign to derail the government by violent grass roots attack, bringing the beleaguered regime almost to its knees.

The security forces’ reaction was brutal and the enormity of crackdown led some people to label it as ‘a reign of terror’.

The theme of Anil’s Ghost needed the mind-boggling violence as its backdrop but in Selvadurai’s Hungry Ghosts it is just a passive distraction. We don’t hear bomb explosions or violent raids by the LTTE in capital Colombo. Except for an occasional army checkpoint and the killing of an employ at a human rights organization, the violence is virtually absent in Hungry Ghosts.

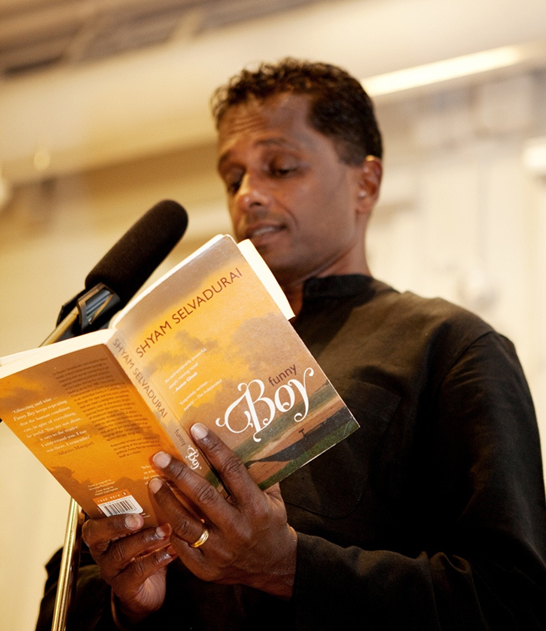

Shyam Selvadurai opening SLWB Samadhana reading series. - Picture SLWB

Instead, what the author offers usis the ‘violence’ of Shivan’s life (he nearly drowns himself in the frigid Vancouver sea and his Sri Lankan lover Mili meets a violent death because his sexuality is not accepted as normal in a country that can jail a man for 10 years for homosexuality), his troubled relationship with people around him, his conflicts and their aftermath.

In Funny Boy, British writers’ influence is quite evident in Selvadurai style, particularly that of George Eliot. In his school days the syllabuses in high schools and universities concentrated heavily on British literature.

The protagonists in both Funny Boy and Hungry Ghosts are forced to accept their homosexuality as a handicap while living in Sri Lanka and adapt their lives to survive the hostile outcome. They remind me of Philip in Mill on the Floss whose physical deformity shapes his life and relationships with people close to him.

The strength of Selvadurai’s fiction lies in his flawless characterization. Grandmother Daya (means kindness in Sinhala), who is the epicenter of family conflict, is a true to life Sri Lankan middle class matriarch, lost between her greed to pile wealth by exploiting her poor tenants living in her ramshackle houses and her obsession with gathering merits to make her after-life better!

Though remaining in the sidelines at the beginning of the novel, Daya rides to the centre of Shivan’s life with her love-hate relationship that ultimately made him realize that she is the only person in his life who loves him dearly.

Selvadurai’s meticulous characterization picks up even minor details of body language to etch feelings and the moods of the characters in particular situations.

One reason for this attachment may be that Shivan’s physical features remind her of her dead husband Charles whom she describes as the love of her life. She even takes the risk of plotting to kill Shivan’s gay lover in the belief that it can make life better for her grandson. Michael, Shivan’s partner, born and raised in Canada, wants to have a normal relationship but finds Shivan’s family and cultural baggage beyond his comprehension.

Shivan’s mother is the most liberated character in the book willing to give and take with no strings attached and resigned to make life happy with whatever little she has. Even minor characters like Shivan’s sister Renu, ruffian-turned politician Chandralal, Rosalind the ayah, carry the layered narrative fitting quite naturally to the action. The characters are not forced upon the reader. They are carved into the natural flow of the narrative, a rarity in fiction of such magnitude and complexity.

Selvadurai’s meticulous characterization picks up even minor details of body language to etch feelings and the moods of the characters in particular situations.

Little things like how one holds a teacup or shifts his gaze reveals a whole lot of hidden meanings and moods. If we examine carefully the mannerisms of Michael’s parents and Shivan’s mother and sister they are poles apart. These characters who are born into two distinctly different cultures, look at similar situations in different ways. The author has taken meticulous care to draw parallels and opposites resulting from this culture clash.

Like Funny Boy, Hungry Ghost may be partly biographical. For instance, the way the newly-immigrated Shivan looks at Toronto, the city’s mad rush to cash in on the immigrant waves by offering shoddily-constructed houses, early Tamil immigrants exploiting their own kind to make a fast buck, overt racial bias, and the chaos in the emerging gay life in Toronto may have been drawn from his own diary. Shivan wins readers’ sympathy for his life’s inescapable ‘karmic’ effects (shades of Thomas Hardy) that shape his battles.

He is a lone fighter not willing to give up and wins at a heavy emotional cost. At the end he goes to his ailing grand mother’s bedside to look after her, symbolically vacuum cleaning his life for a new beginning. Hungry Ghost is the best book so far by this young Sri Lankan-born writer who has shown maturity in his craft over the years and shows promise of a great future. At 48, night is still too young for him.